The Watchdog is flagging the dangers of graft on all PHL health and education costs

By Chloe Mari A. Hufana again Adrian H. Halili, Journalists

The risk of corruption in the Philippines’ 2026 national budget extends beyond infrastructure to health and education spending, a budget watchdog said, warning that weak safeguards during implementation could expose some of the government’s biggest social programs to political interference.

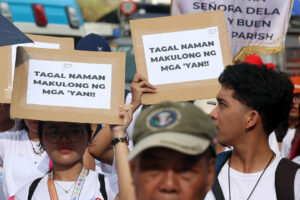

Social Watch Philippines said the allocation approved by Congress for educational and health care facilities warrants close scrutiny as the P6.793-trillion General Appropriation Act moves from legislation to execution, especially after the recent graft scandal involving public projects.

“Corruption risks are not limited to infrastructure organizations,” said Alce C. Quitalig, senior budget analyst at Social Watch Philippines, via Viber. “The education and health sectors also contain questionable budget provisions that need to be carefully scrutinized.”

The group flagged the increase in funds added by lawmakers to the basic education program of the Department of Education over the original proposal of the agency, and the allocation of medical assistance of the Department of Health (DoH) to Poor and Indigent Patients approved in the bicameral congressional phase.

President Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr. signed the 2026 budget on Jan. 5 after objecting to P92.5 billion in unplanned funds. The appropriations bill was passed amid growing concerns about corruption following revelations about the misuse of public works funds.

Another change included in the budget was the removal of political guarantees from the DoH scheme, which eliminates the need for approval to receive hospital loan assistance. The DoH will issue revised guidelines in February to streamline procedures, increase coverage and reduce political influence in aid distribution.

Education also received the largest share of the budget, in line with constitutional requirements, with a record share of P1.345-trillion. The health sector was allocated R448.125 billion, which is the highest in history.

The risks of corruption in these sectors are systematic given the level of procurement, processing and documentation involved, said Hansley A. Juliano, a political science lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University.

“Even in the 1990s, corruption and price gouging continued, money laundering or facilitation,” he said via Facebook Messenger. He added that the rush to deliver health and education services creates pressure where laws can be bent.

As the work begins, Mr. Quitalig said the President has broad authority under the budget to enforce accountability, including the power to freeze or withhold spending when the public interest requires it. The challenge, he said, is in upholding the law.

The main problem is implementation – whether these provisions are implemented sincerely or are avoided, ignored or violated in practice, he pointed out.

Social Watch Philippines called for stronger citizen oversight, calling for wider use of budget monitoring, procurement monitoring, participatory research, and data transparency. It also pushed for deep institutional reforms, including full civil society membership on federal bids and awards committees, the passage of a Freedom of Information law, and a transparent national budget platform that tracks results.

While there are safeguards in place, the group said restrictions on the distribution of financial aid and restrictions on the inclusion of political products in government projects remain weak, warning that poorly drafted rules could entrench aid practices if left unchecked.

Sustainable accountability, it said, depends on strong enforcement by the Executive branch, continuous monitoring of the law and active public participation in monitoring how funds are spent.

‘LEGAL CORRECTIONS’

The Senate should start examining projects that involve large budgets and weak oversight mechanisms, says Ederson DT. Tapia, a professor of political science at the University of Makati.

“These include large transport projects with recurring costs, digital and ICT systems (information and communication technologies) bought under the claims of innovation but protected from scrutiny, and climate-related infrastructure where urgency often replaces accountability,” he said in a Messenger interview.

The Senate Blue Ribbon Committee may also look at social programs and other types of infrastructure, including public roads, said Anthony Lawrence A. Borja, a professor of political science at De La Salle University.

“It should extend to other social projects like social programs,” he said via Messenger. “Looking at other types of infrastructure would also be good, especially public roads.”

Mr. Borja added that the Senate body should take a broader approach and coordinate closely with government investigative agencies.

“If the Senate committee wants to show that it is committed to accountability, the investigation should be thorough and consistent with the work of agencies such as the Office of the Ombudsman,” he said.

The Blue Ribbon Committee has been investigating irregularities in flood control programs since August, following reports that government officials and top law enforcement officials may have received billions of pesos in compensation from flood relief funds.

The hearings have become a key clue in the government’s anti-corruption campaign, with evidence used as the basis for indicting officials and contractors.

Mr. Tapia said that the Senate team may have fulfilled its role of fact-finding in the flood control projects and should begin to close the investigation.

“The closure should be accompanied by a clear definition of responsibility, a written referral to law enforcement agencies and a short list of legal remedies,” he said. Otherwise, the end is just another way to forget.

He warned that extended hearings could disrupt the Senate’s legislative work, including changes related to the budget process, climate change and social protection.

“Excessive investigations would dramatically reduce the ability of Congress to correct its disclosures,” Mr. Tapia. “We must pay more attention to building and strengthening institutions.”

Joy G. Aceron, activist-director of the transparency group G-Watch, said the investigation into flood control is still important but now must focus on policy failures.

“The Senate must start interfering in the policy issues that led to the looting, as the Senate hearings are finalizing the law,” he said via Messenger.

He said lawmakers must examine weak accountability systems and the way contractors use procurement laws, adding that both areas require legal action.

Senator Panfilo “Ping” M. Lacson, who heads the Blue Ribbon Committee, said the hearing will resume on January 19.

The next hearing will deal with the so-called Cabral files, which allegedly contain details of budgets, infrastructure projects and benefits related to flood control and other public works.