State legislators have targeted the development of Santa Barbara. Now, the fall

Angry residents of Santa Barbara jumped into action when development plans emerged last year for a long-roofed residential complex.

They complained to city officials, wrote letters and formed a non-profit to try to block the project. However, the developer’s plans are moving forward.

After that something strange happened.

Four hundred kilometers away from Sacramento, the makers of the collaboration in the country are silent in bad language in the bad budget document that requires the study of the environmental impact of the proposed development – What lawyers of Advocate Abospeates were trying to block the project.

The legislation, Senate Bill 158, was signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newlom, did not mention the Santa Barbara Project by name. But the provision was defined and specified that it could not apply to any development of the state.

The fallout was swift: The developer sued the Legislature and Santa Barbara, the powerful new President of the State Senate, was scrutinized for his role in the Bill.

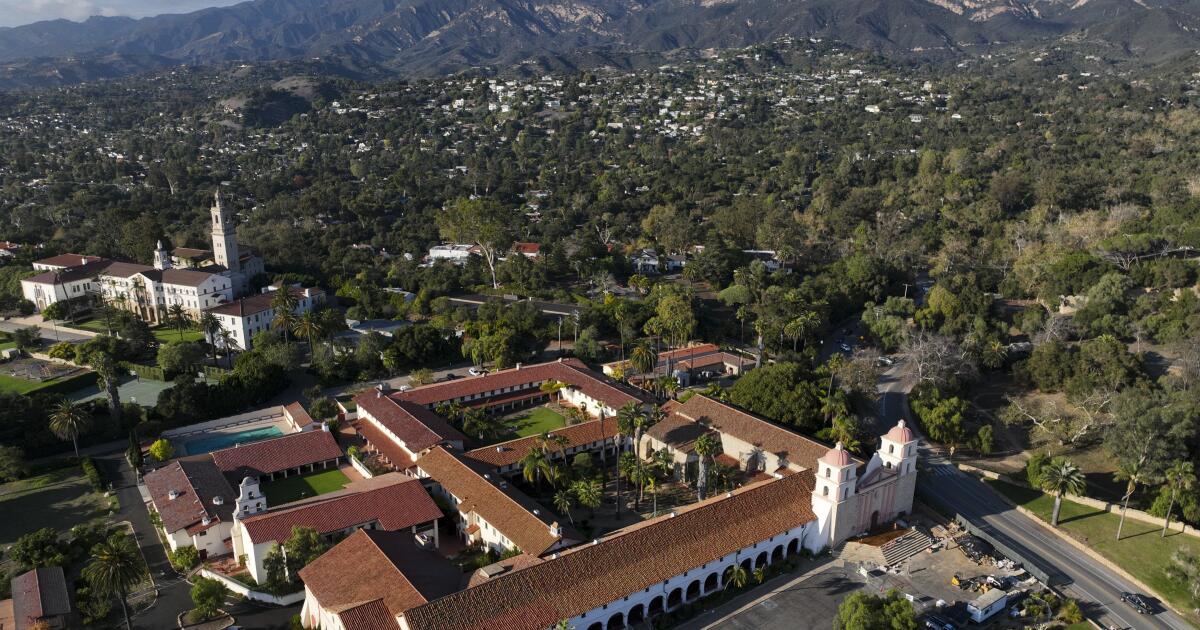

The current property is located in a proposed eight-storey apartment block.

(Kayla Bartkowski/Los Angeles Times)

The saga highlights the growing influence of the governor and state legislature in local decisions, and the battle between the cities and Sacramento to address the critical housing shortage.

Faced with California’s high housing and rental costs, state leaders are increasingly passing new executive orders that require cities and counties to accelerate new housing construction and ease barriers to developers.

In this case, the law that oversees Santa Barbara’s development does the opposite by making it harder to build.

‘VISIBLE HIGHRARE’

The fight began last year after developers Craig and Stephanie Smith laid out ambitious plans for an eight-story apartment project with at least 250 homes at 505 East Los Olivos St.

The five-acre site is located near Santa Barbara’s old mission center, which draws hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

In Santa Barbara, a slow-growing area where most apartment buildings are two stories, the Los Olivos project was seen as a skyscraper. The mayor, Randy Rowse, called the proposal “Good night,” according to local media outlet Noozhawk.

But the developer had an advantage. California law requires cities and counties to develop growth strategies every eight years to address those rates in California. Jurisdictions are required to serve areas where housing or human settlement may be added.

If cities and regions fail to develop plans that span eight years, the so-called “Builder solution” kicks in.

It allows developers to go beyond the limits of the design space and build larger, denser projects with respect to lower or lower installed units.

Santa Barbara was still working with the state on its housing plan when the deadline passed in February 2023

Opponents of the proposed Santa Barbara development, clockwise from bottom left: Cheri Rae, Brian Miller, Evan Minogue, Tom Meaney, Fred Sweeney and Steve Forsell.

(Kayla Bartkowski/Los Angeles Times)

A month before, in January, the developers presented their plans. And since they put in 54 basement units, the city couldn’t turn down the project.

“The developers were playing chess while the city was playing checkers,” said Evan Minogue, a Santa Barbara resident who opposed the development.

He said older generations in California are resisting change, leaving the state to go in with “one-size-fits-all, one-size-fits-all policies to force cities to do something about housing.”

Santa Barbara, an affluent city that attracts celebrities, bohemian artist types and environmental activists, has a long history of fighting for a small-town feel.

In 1975, the city council adopted a plan to reduce development, water use and traffic, and keep the city’s population at 85,000. In the late ’90s, Michael Douglas – alum of UC Santa Barbara – Donated Money to save the largest area of the ocean.

Hemmed in the Santa Ynez mountains, this town is dominated by mixed-use buildings and single-family homes. Media’s home is valued at $1.8 million, according to Zillow. A city report last year projected a need for 8,000 units, primarily for low-income families, in the coming years.

Stephanie and Craig Smith, developers of the project at 505 East Los Olivos Street.

(Ashley Gutierrez)

Assemblymember Gregg Hart, whose district includes Santa Barbara, supports language in the budget bill that requires an environmental review. He doesn’t want to see the proposed development tower over the old work and blames the building maintenance code for introducing it.

“It’s a great illustration of how broken the ‘Builder Memefield’ system is,” Hart said. “Promoting projects like this from the ground up supports building humanity in Santa Barbara.”

Similar pushback was seen in Santa Monica, Huntington Beach and other smaller cities as developers scrambled to implement Richity’s Reching Ordinance. A notable example recently played out La cañada flintridgewhen developers pressed ahead with an 80-unit condominium project on a 1.29-ancre lot despite fierce opposition from the city.

However, the opposition law does not pay for the development of the review under the California Envisionive Environmental Act, known as CEQA, a basic state policy that requires the study of the effects of the project on traffic, air quality and more.

The developers behind the Los Olivos Street project want to avoid environmental reviews, however, because of a new federal law that allows many urban projects to avoid such requirements. Assembly Bill 130, based on legislation introduced by Assemblymember Buffy Wick (D-Oakland), was signed into law by Nebandom in June.

When Los Olivos developers asked City officials about AB 130 for their project, Santa Barbara’s director of community planning told them July 2025 is when a CEQA review is needed. AB 130 does not apply if the project is planned near a Creek and Wetland habitat, or other environmentally sensitive area, the director wrote.

Months later, the state legislature passed its budget report that needs to be revised.

Santa Barbara residents who oppose the project say they did not ask for the Bill.

But if the review finds that traffic from the development will cross fire escape routes, for example, they can have a good time fighting the project.

“We don’t want to come across as nimbys,” resident Fred Sweeney, who opposes the project, said, referring to the saying “not in my back yard.” Sweeney, an architect, and others started a non-performing action for growth and equity to highlight the Los Olivos project and a second planned by the same developer.

Standing near the project site on a recent day, Sweney pointed out how cars were lined up on the main road. It wasn’t even rush hour, but the traffic was already building.

A truly astonishing bill

Deep burial in the senate Bill 158, this bill passed by the state legislators addressed to the Los Olivos Project, it is mentioned in the federal law where there are urban houses. Senate Bill 158 specified that certain developments should not be excluded from this legislation.

Development “in a city with more than 85,000 people but less than 95,000, and within the area of between 440 and 455,000 people,” and will also be close to history, full of tears, not released.

According to the 2020 census, Santa Barbara has a population of 88,768. Santa Barbara County has a population of 448,229. And the project sits next to the ferry and the santa barbara mission.

A controversial development is appropriate.

Monique Limón is President Pro Th TET of the California State Senate.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The representative of the Senate Meover Prom Monique Limón told the compromise that the senator is involved in ensuring that the language of the release.

During a tour of an avocado farm in Ventura last month, Limón declined to comment on his role. He presented the case and directed the questions to atti. Gen. Rob Bonta’s.

Limón, who was born and raised in Santa Barbara, confirmed that he spoke with Sweeney — who started the anti-development benefit — about opposition to the development.

The Los Olivos Project ‘was involved in a lot of community and participation, “he said. “Regarding the response, from what I understand, I read the articles, there are more than 400 people who tested us in it … it is a very public project.”

Limón also defended his housing record.

“All the pieces of legislation that I revise or revise, I do so based on the needs of our country but also with a public lens that I am independent of – whether that is to preserve housing, education, environmental protection or other issues that find my wheel,” said Limbión.

Developers filed a lawsuit against the city and the state in October, saying SB 158 targets one project: it. As a result, it was meaningless under federal law, which prohibits “special law” targeting a single person or property.

Existing home in proposed development area.

(Kayla Bartkowski/Los Angeles Times)

The suit says that Limón promoted and introduced this Bill through the State Senate, saying that it should be dismissed and questions the Environmental Review required, which may have added years to its line and its millions.

Stephanie Smith, one of the developers, told the times that the Bill was born from “protests of wealthy homeowners, many of them, promote housing until the proposed housing is in their neighborhood.”

“As a student who was a stay-at-home student who worked full-time and lived in my car, I know what it means to struggle to afford housing. Living without safety or dignity gave me a core belief that housing is a basic, basic right,” Smith said.

Public policy advocates and experts have expressed concern about land brokers using their power to enter local housing projects, especially when they record rules in documents that have been put to everyone in the government.

“It’s hard to ignore when a law is written in a slightly modified form — especially when the language seems to be outdated with little public service,” said Sean McMorris of the California government group Common Cause. “The bills have been developed in such a way that they encourage public criticism of the legislative process and the motivations behind the more focused policy.”

UC Davis School of Comfor Professor Chris Elmendorf, who is in charge of housing policy, called the specific language of the Bill “and asked if it could survive a legal challenge.

He expects to see more requests for exemptions from state housing laws.

“Local groups that don’t want the project to go to the Legislature for relief that, in the past, would have gone around to their city council,” Elmendorf said.

UC Santa Barbara Retudent Enri Lala is the founder and President of the student housing group. He said the bill was against the recent housing movement in the area.

“That’s normal,” said Lala. “This is not the kind of travel we want to see again in the future.”