What is La Niña? SoCal hit with record Start of rainy season

Californians can be driven out of the weather by confusion.

Scientists in October said that La Niña had arrived, many associated with dry conditions, especially in the south.

But instead we got a very wet season — at least so far — with rain bringing much-needed moisture to the brush, possibly ending the fall fire season, and helping to keep the state’s reserves in good shape.

So what happened?

It is in the fact that La Niña they are common To connect with the dry water year, which is made for the national climate explains from Oct. 1 to September 30.

During La Niña, sea temperatures in the Point Central and Eastern Ocean cool. And the jet stream – the western group of air in the atmosphere – changes to the north. This often forces winter storms toward the Pacific Northwest and Canada, while leaving swaths of California drier than average, especially in the south.

La Niña winters are usually located in the southwest.

(Paul Duginski/Los Angeles Times)

Of the 25 La Niñas since 1954, 15 brought normal conditions to California.

But La Niña “doesn’t always mean drought,” said the meteorologist, professor emeritus at San Jose State University.

In fact, apart from the seven La Niñas observed in the last 15 years, three were wet when it rained.

Heavy storms hit California across the country in 2010-11, creating so much snow that skiers complained.

The 2016-17 la Niña period brought about 134% of the annual rainfall. It was the second weirdest season in terms of the state’s rainfall and California’s punishing drought at the same time.

Water flows over a damaged highway in Lake Oroville and the Troubles River on February 11, 2017.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

So much rain fell that time that California’s second largest reservoir, Lake Oroville, overflowed. The mass evacuation prompted fears that the retaining wall could collapse, sending floodwaters rushing into the communities below – a disaster that was eventually averted.

But in San José, floodwaters poured out of Coyote Creek and into many homes. The snowpack was so heavy that skiers were sailing down Skiini’s slopes in bikini tops and underwear in June.

The 2022-23 season was another DREWETS-BUSTER, marking the end of California’s three-year streak on record.

Torrential rains cause near-sanitary landslides in an apartment complex in San Clemente in March 2023.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

However, California agents who lived in the 1980s and ’90s often think of tips about La Niña and its well-known counterpart, El Niño – with a previous day that appears “Demald of Epic rains and floods.

The truth is that La Niña and El Niño are not the only predictors of weather patterns leading up to California’s rainy and snowy season.

“El Niño / La Niña forecasting is like poker, where you might have a good hand, but when you draw the last card, you don’t get what you hoped for,” said Marty Ralph, director of the water center at the OcerpPography Center at UC San Diego.

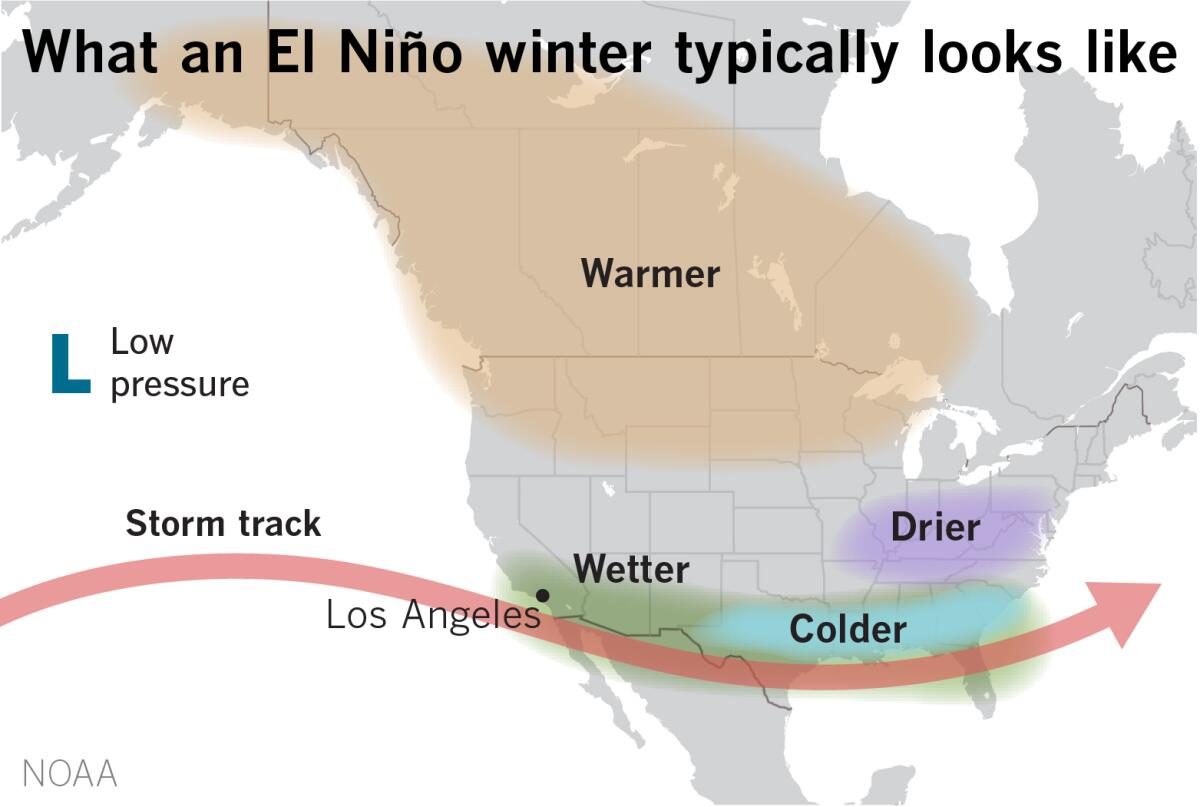

During El Niño, ocean temperatures rise in the central and eastern Pacific. The jet stream is moving south, pointing to a possible fire hose heading toward California, especially in the southern part of the state.

This map shows the typical results of the El Niño pattern in winter in North America.

(Paul Duginski/Los Angeles Times)

“We saw in the ’80s and ’90s a really good correspondence between El Niño/La Niña behavior in the southern California Anomalies – wet el niños down here, and dry la Niñas,” Ralph said. “But it’s interesting, when we moved into the 21st century, somehow, something changed.”

Other El Niños have been popping up in California, too. The driest water year in Downtown Los Angeles’ recorded history, 2006-07, occurred during El Niño. Then there was the “Godzilla” El Niño before the 2015-16 water year that led to a mild winter in southern California and either the middle or upper arms of the north and rain in the north and mid-ocean.

Ralph and his colleagues are trying to find out why they are in other countries without water for years, as they put it, “remedial” – working with “hard” expectations of what they can expect.

What they found is that La Niña and El Niño may influence some storms that hit California — but only seasonal variations from Alaska or northern Hawaii, Ralph said.

What La Niña and El Niño affect, however, are the “rivers of the sky,” which carry heavy rain and snow to California from the tropics, Ralph said. The findings were reported in February in the journal Climate Dynamics.

Homes in San José were flooded with epic rains in early 2017.

(David Burow / The Times)

Each armoreric river can carry a water boat. Only four to five will make it to the tropical climate of southern California, Ralph said. Atmospheric currents spawned powerful storms that lashed California this October and November.

The average atmospheric flow carries more than twice the flow of the Amazon River, according to the American Meteorological Society.

Atmospheric rivers, on average, account for up to 65% of annual precipitation in northern California. But it can be a wild year from year to year, with storm surges affecting anywhere from 5% to 71% of eastern California for the year, the report said.

Another study also suggested that the changes are the old rules of La Niña and El Niño, because atmospheric rivers “are said to be increasingly present in the spring of the year,” they wrote.

Classic setup of the “Pineapple Express” Atmospheric River that taps moisture from the tropics.

(Paul Duginski/Los Angeles Times)

Officials have long warned that ongoing climate change could be a whippifornia amid excess rainfall, with the state trending toward isolation, focused on the wettest years.

“La Niña and El Niño are not the only players in this game,” said Nel. “I think we need to add an addendum to that playbook. Part of that is driven by climate change. … There is climate change in the DNA of all progressive climate platforms.”

California saw unusually wet storms this fall due to a persistent low pressure system along the west coast that stretched through most of October and November. That system was able to draw unusually strong winds into the deep tropics and send storms into the U.S., said Jon Gottschalck, chief of the National Weather Service and Atmospheric Administration Center.

The Santa Barbara Airport is on record to start the water year with 9.91 inches of rain, beating the previous record of 7 inches, according to the weather service office in Oxnard.

Since Oct.

Even really and strongly and with the subtlety of Faith Valley National Park they saw the Fettest November on record, recording 1.76 centimeters high of the high centimeters in 1923, according to Chris Weather Service of 1 vegas in Las Vegas.

Las Vegas recorded its September-October period for October-November this year, with 2.91 inches.

The rain over the rest of California was very heavy this time of year, enough to reduce the risk of wildfires, but not so heavy as to cause a catastrophic landscape.

“It’s kind of the Goldilocks of AR,” Ralph said.

But what is wrong is the warm warm way. Ski resorts have complained that recent storms have not produced much snow. A healthy snowpack is the key to California’s water supply, creating an ecy reservoir for the mountains that no longer have man-made lakes.

The same coastal pressure system that helped power recent atmospheric rivers forces winds from the west and west and south. That’s warmer than when the air blows into California, Alaska or Canada.

Because of this, November temperatures are “above normal” for the entire West, said Gottschalck. “There has been rain in northern California … but it is very warm,” he said.

Snow machines are used on the slopes in Big Bear on Thursday. Low snow levels have delayed the opening of southern California ski areas.

(Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times)

It’s the first day of rain and snow and snow and it doesn’t mean “it’s going to be wet all winter,” GottsChalckckck said. “It doesn’t work that way.”

Just look at the 2021-22 season – La Niña. October 2021 was the fourth wettest October in California history, courtesy of a category 5 Atmospheric storm, which is devastating. But the following January-April was such a season in California. In April 2022, California’s snowpack was only 38% of normal.

There are no major rain or snow storms in the forecast from early December in early California so far.

“Recent history has shown us that there is potential for a California winter,” said Karla Nemeth, director of the California Department of Water Resources.